Learnability—A New Imperative for Business Schools

- “Learnability” is a skill increasingly valued by employers—it refers to the capacity of individuals to be self-driven learners who view every experience as an opportunity to enhance their knowledge.

- Curiosity is fundamental to learnability. To teach the learnability skill, we must provoke students’ curiosity by asking them to view every experiential learning activity through the lens of their individual career aspirations.

- By teaching learnability across the curriculum, we instill in students an appreciation for and tendency toward lifelong learning.

It is curious that educational institutions—the so-called “bastions of learning”—do not teach students how to learn. Information about what to learn is freely available, but educational content that teaches students how to learn is lacking. It’s the elephant in the (class)room that deserves far more discussion and action.

At a time when so much knowledge is available at our fingertips at little or no cost, one could argue that teaching students how to learn is especially paramount. It is a meta skill, or higher order skill, that students can use to master any other skill or area of knowledge that they will need during their careers. It is the path to lifelong learning.

This makes it critical that we help our students become continuous, self-driven learners. We must adopt strategies designed to encourage students to view every experience as an opportunity to enhance their knowledge and growth.

A Critical Skill for Career Development

Learnability is particularly relevant in business schools, where much of what we teach evolves over time. Business curricula are primarily driven by changing business priorities, emerging corporate challenges, and new insights from research—we need only look at the number and diversity of elective courses offered in today’s MBA programs, compared to the electives available a decade ago.

It is no surprise that even newly minted business graduates will need to continuously update their skills. AACSB recognizes this reality in its 2020 Business Accreditation Standards, in which Standard 4 asks business schools to use their curricula to help students foster lifelong learning mindsets.

Unfortunately, business schools have been slow to modify or adapt their curricula to address learnability. This is surprising, given that today’s recruiters recognize learnability as critical for career growth and mobility and that companies have begun to assess learnability in their recruiting processes.

Thus, learnability (described by McKinsey & Company as “intentional learning”) is a key determinant of employability, and a driver of career success. Schools ignore this increasingly important skill at their own risk.

What Does Theory Suggest?

How should business schools teach learnability? While there are no simple answers to this question, schools can begin by experimenting with various pedagogical methods to see what works best. They can base this experimentation on research that highlights the conditions under which students are most likely to strengthen their learnability skill:

Courses that emphasize experiential learning. Theory and practice suggest that students are more likely to improve their learnability when they are interacting with the real world. These interactions—which can occur during their internship experiences, project-based courses, and action-learning projects—provide students with opportunities to practice skills in real-world work environments and prepare them for a future of continuous self-driven learning while on the job.

Activities that cultivate “curiosity mindsets.” As Erika Andersen emphasizes in “Learning to Learn,” a 2016 article in Harvard Business Review, curiosity is the key driver of learnability—but it is difficult to teach it to those who are not naturally curious.

Learnability is a key determinant of employability and a driver of career success. Schools ignore this increasingly important skill at their own risk.

That said, it is possible for faculty to provoke curiosity in anyone—for instance, by asking questions tied to students’ individual career aspirations. This approach is one experts recommend as a way to trigger curiosity, as executives Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic and Josh Bersin explain in a 2018 article in Harvard Business Review. As they note, “the best way to trigger curiosity is to highlight a knowledge gap—that is, making people aware of what they don’t know, especially if that makes them feel uncomfortable.”

When professors trigger students’ curiosity, students will be more willing to complete thoughtful reflections—and start down the path of self-driven learning.

Conducting a Pilot Study

In the 2018–19 academic year, I was a faculty mentor for student teams involved in experiential learning at the Asia School of Business (ASB). Located in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ASB operates in collaboration with the MIT Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. Experiential learning at ASB was accomplished through action learning projects, which involved solving real business problems faced by companies.

As a faculty mentor, I applied a modified version of the Gibbs Reflective Cycle to guide my attempt at teaching learnability. I wanted to provoke curiosity in students by asking each member of a team to go beyond the issues connected to the action learning project. I asked them to view the company through the lens of their individual future careers and identify issues that piqued their personal interests.

Students offered diverse responses to this question. For example, on a team working on an operations management action learning project, one student was drawn to an issue connected to the branding of services because she was interested in pursuing a marketing career. Another was curious about employee attrition because of his interest in human resources. And yet another wanted to know more about the leadership style of the manager working with her team because of her own focus on leadership.

Students completed reflection reports on their respective issues of interest and received feedback on their reports from me. By the end of the term, the students had experienced two types of learning: team-based learning from the action learning project, and self-driven learning that individual students had chosen based on their unique future career goals.

Ideally, this process would be repeated throughout an MBA program. That is, every time students completed real-world projects (such as internships, project-based classes, or other company interactions), they would repeat these steps: scan the project’s context through the lens of an individual future goal, identify issues that pique interest, complete an initial reflective journey, receive feedback from faculty, and reflect again after the activity has concluded. Such repetition can lead to habit formation, increasing the likelihood that learnability will lead to lifelong learning.

The response I received from the students was overwhelmingly positive. Because the additional work was driven by their own interests and needs, they told me that they viewed that effort as valuable to their career development.

Teaching Learnability From the Top Down

When it comes to teaching learnability, I believe that educators can take two primary approaches. The first is the “top-down approach,” which is particularly suited for MBA curricula that emphasize action-based projects, internships, and real-world interactions.

With this approach, faculty could focus on experiential learning courses in the curriculum, where they could formalize a model similar to the one I deployed in my pilot. That is, they could ask students to complete four key steps, as described below.

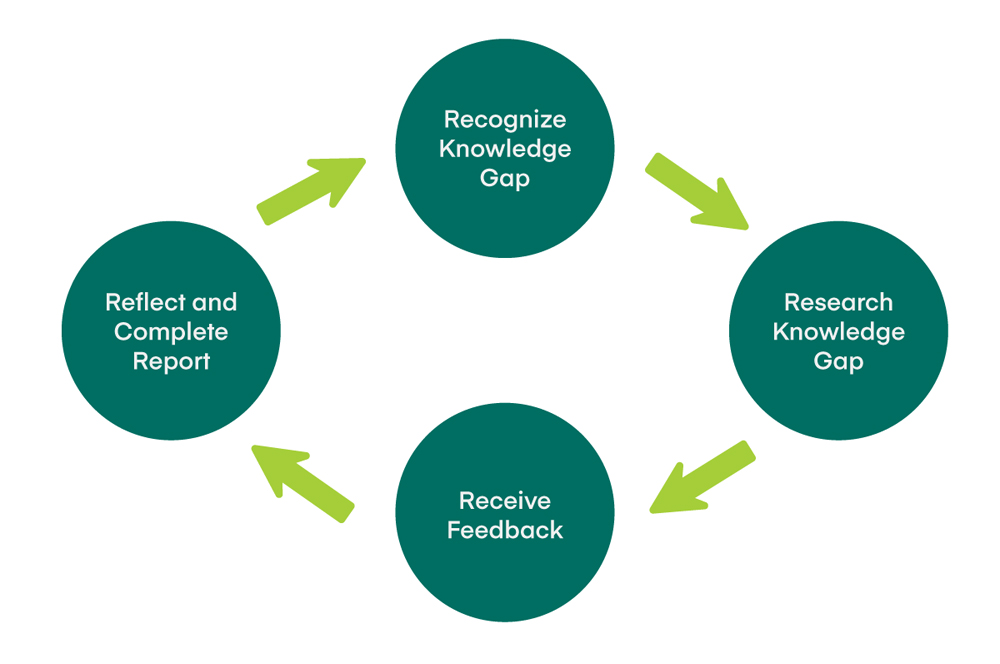

- Recognize their knowledge gaps. Students would be expected to scan the work environment of the experiential learning project through the lens of their career goals and identify issues that pique their interests. The issues students identify do not need to be connected to the specific focus of the project. Rather, the issues simply need to be relevant to their career development and represent gaps in their current knowledge.

In other words, faculty want students to think, “This is something I should know if I am to excel in my career.”

- Research and write about their knowledge gaps. Next, students would research the areas where they lack knowledge and provide faculty with short, half-page-long write-ups on how those gaps might be relevant to their futures. To make this a meaningful and relevant learning exercise, faculty should make students aware that it is in the interest of their career development to ask difficult questions in these write-ups.

- Receive feedback. Faculty would then review these write-ups and provide thoughts and questions for students to reflect upon further. These questions should touch on both “single-loop learning” and “double-loop learning.” Single-loop learning focuses on the issues as they are, whereas double-loop learning encourages students to question their assumptions about “what is” and explore their beliefs about root causes.

- Reflect further and complete reports. Finally, students would complete their reflection-based reports by conducting further research on the single-loop and double-loop learning questions provided by faculty. During this step, it is likely that students will recognize additional knowledge gaps, which would start the cycle again.

The above steps should be required of every student in any experiential learning setting during the MBA program, as a way to help students acquire the learnability skill. Further, students should be exposed to key principles of learning—which my co-author John Mullins and I call the “drivers of learning.” These include strategies such as offering opportunities for reflection, building on past knowledge and experiences, and making learning objectives clear. By integrating these principles into their teaching, faculty ensure that any new learning that students acquire is durable and adaptable.

Teaching Learnability From the Bottom Up

In the “bottom-up” approach, faculty would make learnability an underlying focus across the entire curriculum—this means going beyond experiential learning courses to teach this skill in all (or most) courses. Here, faculty would start by highlighting the foundations of learning—the learning drivers mentioned above—and showing students how these learning drivers are the building blocks for the meta skill of learnability. The value of learning drivers could be explained to students early in the MBA program, possibly during the program’s orientation sessions.

A bottom-up approach still encourages students to identify knowledge gaps that are meaningful to them in their assignments and projects, based on their individual career goals. Teachers could design assignments that encourage students to apply and connect material taught in the class to areas relevant for their future careers. For example, in a class on branding, such an assignment could lead a student interested in investment banking to delve into “brand value in mergers and acquisitions.” A student interested in human resources might identify “the role of HR in employer branding” as a knowledge gap and complete a report on that topic.

By encouraging students to identify knowledge gaps that are meaningful to them, teachers can ensure that learnability becomes ingrained in students, with the likelihood that lifelong learning will follow.

If business schools teach this skill across curricula, students will complete each course having developed two types of learnings. The first type is common to all students and based on the teacher’s learning objectives; the second type is unique to each student and based on his or her career goals.

It is the second type of learning that lays the foundation for learnability. By encouraging students to engage in this process across many courses, teachers can more effectively ensure that learnability becomes ingrained in students, with the likelihood that lifelong learning will follow.

Given today’s easy availability of information and rapid pace of change, the knowledge that business graduates possess is not as important as their ability to continuously learn and update their skills. As a result, learnability has become essential across the board—to recruiters and employers, to students and faculty, and to accreditation agencies such as AACSB.

As educators, we are always striving to prepare students to succeed in the future of work. Now that we know that learnability is increasingly a key determinant of students’ employability after graduation and a driver of their long-term career growth, we can more successfully set the stage for students to embrace lifelong learning.