A New Lens on Societal Impact

- The Australian Business Deans Council Societal Impact Framework provides researchers a foundation for scoping, planning, and capturing the societal impact of their research.

- By communicating how they address local and global challenges, business schools can demonstrate their relevance and accountability.

- The framework can be used to contribute to a business school’s reputation and provide supporting documentation for accreditation efforts and funding applications.

When business schools articulate their relevance to the wider community, one of the most important factors they must consider is the impact of their scholarship. Yet business schools do not always systematically capture, communicate, celebrate, or reward the societal impact generated by their faculty’s research efforts.

That needs to change. Today, as we see a decline in public investment in research and hear questions about the value of business as a discipline, it is more important than ever that schools demonstrate how their scholarship creates positive change in the world. The question is: How?

Three Obstacles to Overcome

Business schools face three main challenges when trying to generate and gauge societal impact:

It’s difficult to track. While scholarly impact is relatively easy to measure through journal articles, books, h-indexes, and citations, societal impact is much more difficult to track because it lies outside these traditional measures. And yet, for research to drive meaningful change, academic knowledge must be transferred beyond the scholarly community to external stakeholders, including industry, government, and the broader community.

It follows an indefinite timeline. Societal impact doesn’t happen instantaneously. It might be years or even decades before cumulative research activities lead to measurable outcomes. Therefore, to assess the impact of academic research effectively in the real world, scholars need to adopt a long-term perspective.

It’s unpredictable. It is difficult for schools to forecast what kind of research will have an effect and when. That’s because societal impact typically results from a variety of direct and indirect activities—and sometimes it occurs even when it was unintended. While this means that, theoretically speaking, societal impact can be generated from many of a school’s diverse activities, the reality also makes it difficult for researchers or administrators to plan for it.

Instead of trying to identify research activities that generate impact, schools should highlight clusters of co-creation activities between researchers and stakeholders.

To help schools overcome these three challenges, the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) has developed a new framework that enables academics to capture, compare, and map the societal impact of their research. It was designed in consultation with ABDC member schools, as well as its Research Directors Network (BARDsNet).

The ABDC Societal Impact Framework is grounded in a productive interactions perspective, which posits that societal impact arises from meaningful, reciprocal interactions between researchers and stakeholders. It suggests that—instead of trying to identify discrete research activities that generate impact—business schools should highlight interrelated clusters of co-creation activities between researchers and stakeholders. While these stakeholders could be located within academia, they are more typically organizations, governmental agencies, and end beneficiaries of research.

Five Stages That Lead to Impact

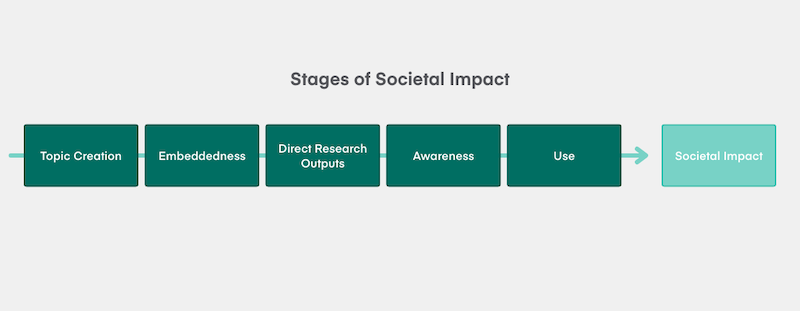

The framework builds a visual indicator of societal impact by tracking the engagement activities of different stakeholder groups—researchers, businesses, not-for-profit organizations, governments, and beneficiaries along the societal impact pipeline. These five stages are topic creation, embeddedness, direct research outputs, awareness, and the use of thought leadership. (Our white paper outlines in detail the activities associated with each stage and stakeholder group. For this article, we’ll illustrate the five stages of the academic impact pipeline.)

Although it is often assumed that societal impact begins with the generation of new knowledge, that is not always the case. Each of these five stages can lead to positive change:

Topic creation. This occurs when researchers and other stakeholders identify a real problem and look for ways to address it together. They might choose to create a new research center or apply for grant money to support a project that addresses a grand societal challenge. Sometimes this effort happens because various stakeholders were involved in a previous productive interaction that indicated that an identified research topic would be worth pursuing.

Embeddedness. When researchers participate in hackathons, provide consulting services, join design sprints, or accept industry secondments, they are directly engaging with external stakeholders. In this way, they embed themselves in efforts to address societal problems—and they take crucial steps toward developing relevant thought leadership.

Direct research outputs. White papers, book chapters, practitioner textbooks, and research articles are all knowledge artifacts of thought leadership that result from the research process. Direct research outputs are deemed productive when they are digestible by different stakeholder groups.

As an example, practitioners rarely read an academic research paper, but they’re likely to read a white paper and implement its suggestions. That’s particularly true if they have been involved in the research leading to the paper’s publication. As a result, co-creation becomes a core thought leadership activity that helps bridge the gap between scholarly research and society.

Although it is often assumed that societal impact begins with the generation of new knowledge, each of the five stages of research can lead to positive change.

Awareness. To generate societal impact, it’s paramount for a school’s thought leadership to leave the realm of academia and meet the outside world. Scholars might generate awareness of their research outputs by putting videos on YouTube channels, publishing articles in The Conversation, or participating in radio interviews.

Use. In this stage of societal impact, thought leadership ideas are adopted by external stakeholders. Perhaps these ideas are cited in policy use or implemented by end beneficiaries. This crucial stage is where research leads to change.

Examples of Positive Change

To trace the frequently nonlinear path of impact, we began interviewing Australian and New Zealand business faculty about how their research has contributed to societal good. Here are three examples of how scholars are creating positive change:

They’re tackling financial injustice to bring about tax reform. A researcher at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney investigates the experiences of disadvantaged people who suffer serious and severe financial hardship related to the tax system. When these individuals don’t have professional advisors to help them, they can fall victim to debt cycles, or “tax policy-induced poverty,” that can ripple to other dimensions of their lives.

By providing free tax advice through the UNSW Business and Tax Advisory Clinic, this researcher has delivered support to more than 500 individuals. The clinic not only has tackled injustices on the front line, but also has generated insights and provided evidence that has shaped government policy, creating both societal and economic impact.

They’re transforming disaster communication warnings to save lives. During natural disasters such as bushfires and floods, timely and effective communication from emergency services can save lives and minimize damage to communities. Yet, in Australia, natural hazard warnings have been structured by operational risk classifications that are not easy for community members to understand and translate into action.

ABDC’s new framework reflects the idea that a school’s impact can be gauged by how deeply and meaningfully its researchers engage with end beneficiaries.

Researchers from the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Brisbane have worked with emergency service stakeholders to develop resources that enable public information teams to deliver clear, behavior-focused messaging during natural disasters. These evidence-based communication tools have generated societal impact by reducing the environmental, human, and economic toll of natural hazards.

QUT’s outputs are now considered the gold standard in disaster communications. Their impact extends beyond Australia as they have been mentioned in the United Nations PreventionWeb and by the World Economic Forum.

They’re enhancing the coordination of housing, health, and social care. In Australia, today’s community housing organizations go beyond providing homes. They also foster social inclusion and strengthen communities by coordinating services such as family violence support, mental health care, and refugee assistance. Yet success is still gauged by historic housing-only metrics.

Researchers at RMIT in Melbourne evaluated the true societal impact of these organizations by measuring their contributions to social cohesion and service innovation. Researchers identified the barriers that make it difficult for organizations across the sector to share policy innovations. This research has enabled agencies to demonstrate real impact, secure government support, and reduce service silos, leading to better long-term outcomes for tenants.

Researchers from RMIT continue to engage in policy advocacy by providing evidence to address systemic challenges in community housing across multiple Australian states.

Reputations and Relevance

Measuring societal impact is not an easy task. ABDC’s new framework, grounded in theory and tested in practice, reflects the idea that a school’s impact can be gauged by how deeply and meaningfully its researchers engage with end beneficiaries. When schools track the productive interactions between researchers and relevant stakeholders, they will be better able to capture their societal impact and share it with all stakeholders.

And as they spread the word about how their research has reformed policies or improved lives, schools enhance their reputations and ensure their ongoing relevance within their communities.