Talking Through the Turmoil

- Public health emergencies, climate change, and demographic shifts are causing rising geopolitical tensions that can negatively impact business and society.

- Business schools need to produce graduates with the “contextual intelligence” to handle the ever-changing political, economic, technological, and environmental landscape.

- A course at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill provides a safe space for students to engage in courageous conversations on politically charged issues of critical business importance.

How can business schools prepare students to be successful leaders in a world where issues embedded in culture wars are having a growing impact on business viability, profitability, and competitiveness? This is a critical question at a time when corporate leaders openly admit that they are woefully unprepared to deal with a range of politically sensitive issues.

Many of the tensions are caused by health and weather concerns that are becoming more frequent and more global in nature. The COVID-19 pandemic was a worldwide public health crisis, and climate change is triggering adverse weather around the globe. These developments are sparking growing labor activism and disrupting population settlement, work patterns, and global supply chains for a wide range of goods and services.

Additional conflicts are caused by demographic shifts as regional populations grow, decline, and redistribute. India reportedly has replaced China as the country with the most people. Japan’s population has been waning for some 16 years; Europe’s population is aging; and fertility rates are down in South America. Russia’s war on Ukraine has contributed to a refugee crisis in Europe, and more than 18 million internal refugees have been displaced in many African countries as citizens grapple with low employment opportunities.

All of these factors have provoked nationalist and populist movements around the world, accompanied by heated discussions about how governments and corporate leaders should respond. For instance, in America, changing demographics have prompted polarizing debates about international migration, white population replacement, marriage equality, reproductive rights, gender pay equity, gender diversity, and affirmative action.

As geopolitical tensions mount, corporate recruiters are searching for talent that can “groove on ambiguity.” That is, they are consciously looking for leaders who are capable of successfully navigating an ever-changing, diverse array of challenges at the intersection of business and society.

Preparing for a VUCA World

To prepare those leaders, business schools frequently offer concentrations and elective courses in social enterprise, inclusive leadership, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. Even so, as an article in Worth asserts, “Business schools aren’t teaching the next generation of leaders about the real-life push and pull of operating in an increasingly politicized and polarized operating environment.”

Many business professors hesitate to incorporate politically sensitive content into their courses because they fear blowback or retribution. Others have legal reasons for not discussing such topics. For instance, in some states in the U.S., laws and legislative proposals prohibit higher education institutions from taking positions on controversial issues.

Still other professors simply don’t have the right teaching tools at their disposal. Case study discussions, global study experiences, team-based projects, elective activities, and presentation courses will not do enough to develop leaders who can handle a business environment that is volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA).

No matter what functional areas students choose to study, they will enter careers that will require them to manage political and economic turbulence. It’s essential for business schools to equip students with the leadership skills and tools they will need to help corporations successfully navigate a new normal characterized by “certain uncertainty.”

Most urgently, business schools must produce graduates with contextual intelligence—keen awareness, knowledge, and understanding of the ever-changing geopolitical, economic, technological, and environmental landscape. When leaders can strategically leverage this awareness in real time, they minimize the likelihood that they will be blindsided by unanticipated change.

Corporate recruiters are looking for leaders who are capable of successfully navigating an ever-changing, diverse array of challenges at the intersection of business and society.

As a corporate communications executive observes in the Worth article,“MBA students need exposure to grey issues at the crossroads of corporate strategy, political acuity, and public relations.” It’s critical for business schools to help students develop discernment skills, cultural sensitivities, and a broad set of communication tools that include storytelling, active listening, and thoughtful questioning.

To achieve these objectives, schools need to make curricular changes across the functional areas of study. They must engage students in critical and reflective discourse about politically polarizing issues that increasingly affect business viability, profitability, and global competitiveness.

Holding ‘Courageous Conversations’

At Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, we have recognized this urgent need for curricular change. As one way to meet that need, the two of us have experimented with an innovative instructional approach in an elective course on leadership that we co-teach in the full-time MBA program. We based the course on two fundamental beliefs:

- Students, as one writer suggested, should attend college to expand their knowledge and increase their curiosity about ideas and opinions different from their own.

- The university’s role, as another writer put it, is “to encourage [and facilitate] debates, not settle them.”

Accordingly, in our course we create a safe space for students to engage in courageous conversations—to openly share diverse thoughts and opinions as well as vigorously debate politically charged issues of critical business importance. Over the past three semesters, we have run the courageous conversation experiment six times.

We extract courageous conversation topics from contemporary business literature. In the most recent semester, we covered four topics of critical business significance: corporate social advocacy, movements for racial justice, return-to-office mandates, and colorism in marketing.

Notably, our goal is not to indoctrinate students in a particular belief or advocate for any specific stance or viewpoint; rather, it is to facilitate honest, respectful, and transparent dialogue. We want students to be fully aware of and informed about the diverse viewpoints—strengths, weaknesses, pros, and cons—that undergird politically polarizing issues.

How It Works

For the actual discussions, we employ a modified version of the fishbowl method of conversation. Students are broken into two groups, one that favors and one that opposes our current conversational topic.

We assign students randomly to opposing positions on the politically polarizing topics we choose. This discourages them from taking a “this isn’t actually my opinion” stance and prepares them for the discomfort that can arise when listening to or participating in a conversation that does not align with their own beliefs.

To prepare for the conversations, students must complete assigned readings representing divergent perspectives on polarizing topics. We also encourage them to gather their own business intelligence, collect evidence in support of their assigned positions, and predict counterpoints.

In class, the teams take turns operating as an in-group talking among themselves and an out-group observing and learning from the in-group conversation. In our version, shown above, we add a question-and-answer period after each in-group conversation and an open, unstructured conversation period at the end of the exercise. The additional question-and-answer periods produce extra layers of complexity, encourage critical thinking, and incentivize careful listening, especially when students function as the out-group.

The unstructured conversational period also allows students to drop their assigned positions and contribute their own perspectives—adding, if they desire, personal stories and reflections that might otherwise not surface from assigned positions. It also provides time for students to synthesize ideas and further disrupt the potential for rigid, polarized thinking.

Creating Safe Spaces

Success in the course hinges on the degree to which students engage in courageous listening to views, opinions, and perspectives that differ from their own. We know that confirmation biases typically shape or drive—and often stymie—discussions of politically charged issues that define the global culture wars. We confront this tendency head-on by requiring students to create “conversation agreements” in advance.

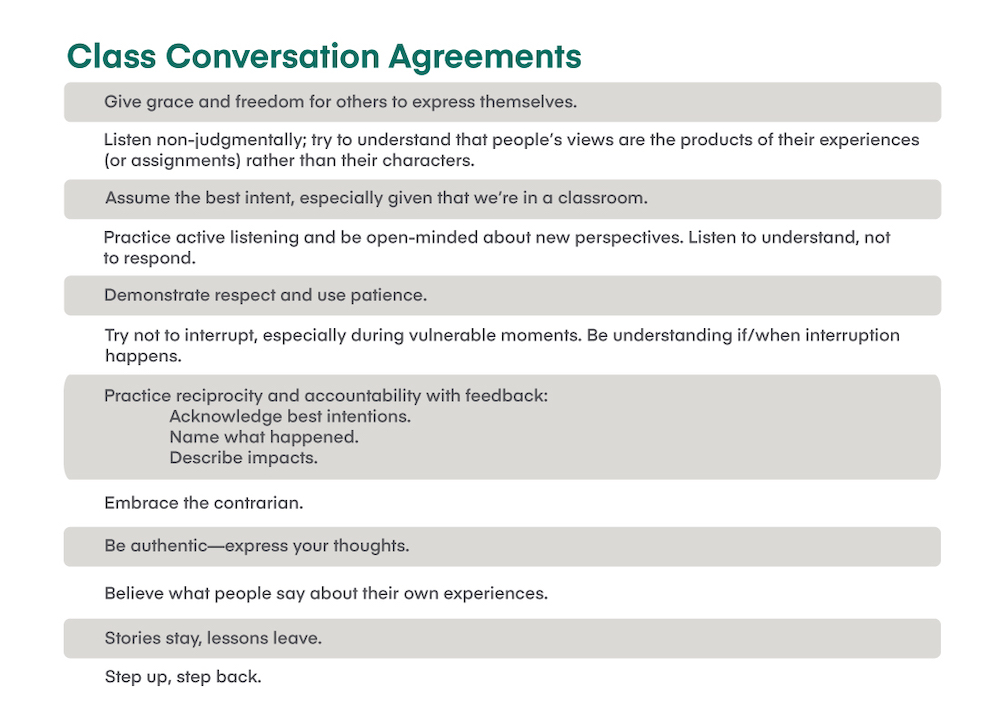

These conversation agreements provide us with a set of shared expectations and productive behaviors to abide by as we discuss polarizing topics. These mutually agreed-upon rules of engagement ground us as a community, and we revisit them several times throughout the course. A list of agreements developed in one of our recent classes appears below.

While we recognize that these agreements will not make all students feel confident, our goal is to provide them with a modicum of psychological safety—a “belief that they will not be punished or humiliated by speaking up with ideas, concerns, questions, or mistakes.”

We are convinced that the creation of an academic safe space is an essential part of this exercise. Without it, students could fear the opinions of their peers—and their professors—and limit their participation, especially their willingness to play the role of contrarian and voice potentially contentious perspectives. By teaching them to find comfort in discomfort, we prepare them to lead in a highly politicized and polarized business environment.

Exploring Competing Perspectives

Based on responses to our courageous conversation experiment, we believe that business students crave educational opportunities and experiences that allow them to explore competing perspectives on politically charged business issues. In a survey of our most recent class, 97 percent of students agreed with the statement, “I found our courageous conversations to be a valuable learning experience.” Here are just a few of the ways they’ve described what they gained from these conversations:

- “I loved the structure of these conversations. They required me to think about how to articulate my positions clearly and effectively while also challenging me to consider the other side of the argument.”

- “I loved the opportunities to explore an alternative perspective. The questions were thought-provoking, and it was interesting to see how they related to the course content. Great way to develop mastery.”

- “Three hours a week is not enough! Also, this needs to be part of the [core] MBA curriculum since the people who need this the most are not here!”

- “I really appreciated learning other people’s perspectives and at the same time sharing my perspectives in a safe and understanding environment. This course should continue and perhaps be made compulsory for every MBA student.”

We have continued to make improvements in the design of the experiment, based in part on our teaching experiences and in part on qualitative and quantitative student data. But like those last two students, we are convinced that the courageous conversation approach deserves serious consideration as a core element of MBA programs.

We believe corporate recruiters will want our students to have the full complement of skills and sensitivities the next generation of business leaders will need to weather the political turbulence that businesses will continue facing well into the future.