Instruction vs. Discovery Learning in the Business Classroom

In higher education, we tend to first provide undergraduate students with instruction, like lectures and readings, before giving them a problem to solve. In the real world, however, business leaders identify a problem first and then seek a solution through a process of discovery.

There is no doubt that lectures help prepare students for the real world. We present essential concepts with ideal applications and effective problem-solving frameworks that students can apply to new situations. A recent study by the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a research branch of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, even suggests that direct instruction results in higher efficacy of learning than discovery-based methods.

The problem occurs when students become accustomed to having thorough instruction and the right answers handed to them by trusted experts. When undergraduates transition into their professional careers, they might struggle unless their managers give them in-depth guidance. According to findings published in the Harvard Business Review, managers tend to support employees who are proactive learners—those who actively seek information about their roles and put effort into making connections with new colleagues.

In contrast to the direct instruction method is the discovery approach, where students learn by doing. For a long time, this has been the prevalent way for educators to train students to think critically and independently as they navigate their own learning processes. However, the approach also has its shortcomings.

We explore the benefits and drawbacks of using either direct instruction or discovery learning in business courses and suggest an alternative for professors to consider.

Direct Instruction Pedagogy

Direct instruction is often considered the “traditional” approach to teaching, as it describes the typical classroom in which a professor directly presents theoretical concepts, provides examples, and gives an assessment of learning. It is a content-centered approach to learning that passively engages students as listeners.

Benefits of Direct Instruction

For students who lack prior knowledge about a subject matter, direct instruction is a great way to teach them to understand and remember foundational concepts. As we know from Bloom’s Taxonomy, a popular framework for categorizing educational objectives, these concepts are the building blocks that help students achieve higher-order thinking skills.

Additionally, the structure provided by lecture-based pedagogy is invaluable to first- or second-year students, as these students often need a lot of step-by-step guidance. Particularly in business courses, newer students enter without a strong understanding of concepts and their underlying frameworks, so they often get lost trying to read between the lines if they are not shown what to look for and where to find it.

Finally, evidence highlighted in the PISA study reveals that teacher-directed instruction achieved higher science literacy rates than an inquiry-based approach. The study, which consisted of a survey and an assessment, was conducted on a large sample size of 15-year-old students randomly selected from different school systems across the world. In the assessment, students had to analyze, evaluate, and draw specific conclusions on scientific data. The results overwhelmingly support teacher-directed instruction methods over inquiry-based approach methods.

Drawbacks of Direct Instruction

Although direct instruction is beneficial for the points addressed above, the teaching method contradicts what a graduate will experience in the business world. In a class, professors typically begin by explaining a theory (the answer) before demonstrating a problem (the question) to which the concept being taught is applied. But in the business world, challenges always start with the problem, and the learning occurs in the journey of researching, investigating, and discovering different pathways to solve that problem. Often employees have to make decisions with incomplete information or insufficient instructions from their managers.

In the business world, challenges always start with the problem, and the learning occurs in the journey of researching, investigating, and discovering different pathways to solve that problem.

Furthermore, direct instruction can limit critical thinking, as the method primarily engages lower-level thinking skills, such as understanding and remembering. Lectures allow students to confidently memorize topics in the same way the professor delivered the information to them. However, as professors are trusted subject matter experts, students often don’t challenge or question the content they are learning and subsequently lose the opportunity to analyze, evaluate, and self-reflect on their understanding of learned concepts.

Last, direct instruction, particularly lecture-style teaching, is a passive form of learning. It contributes to “mind-wandering,” which was the focus of a Harvard University study that found that an increase in mind-wandering during lectures was associated with poorer performance.

Discovery Learning Pedagogy

Discovery learning is an inquiry-based learning method that takes a constructivist approach to education, where students are encouraged to construct their own knowledge through a self-directed learning process—essentially “instructionless” learning. Jerome Bruner, who is often credited as the originator of discovery learning, argues that, in the discovery process, students learn to acquire information in a manner that is most relevant for solving the current problem, which makes insights practical and sticky.

Benefits of Discovery Learning

Learning through discovery enables students to exercise higher-level thinking skills and better retain knowledge as they go through the following phases to learn a business concept:

- Contextualization: Students get familiar with the subject matter on a high level by being confronted with a business problem.

- Exploration and analysis: Students collect data from various resources to analyze the details (for example, trends, formulas, general concepts, variables) of the business problem and teach themselves the relevant information to answer questions and critically evaluate their hypotheses. This is where they go through a self-directed journey to improve their business acumen.

- Drawing conclusions: Upon gathering new insights and refining their understanding of the different variables and models involved in the business problem, students synthesize their discoveries and create their own interpretation of the best solution based on their individual learning processes. That solution is presented to faculty and peers for feedback. Students have the opportunity to leverage the feedback to reflect on their work and conclusions.

As students go through discovery learning, they have a more active role in their learning outcomes, as they must understand granular data and identify how different aspects of a business problem relate to one another to find the optimal solution. As a result, students may become more inspired to learn concepts they do not know and to better understand topics they do know, as they now have first-hand experience working through the discovery process. Further, self-directed learning can boost students’ perceptions of their own capabilities.

One of McKinsey’s findings in its PISA study analysis is that mindsets, such as self-belief and motivation, have an outsized effect on students’ academic performance compared to other influencing variables. Given the huge impact of discovery learning on students’ motivation and self-efficacy, many might infer from this finding that discovery learning is the best solution for improving students’ performance on any learning objective. However, this assumption is not always correct.

Drawbacks of Discovery Learning

Discovery learning can be time-consuming. Students learn at different paces, and professors have limited time to address certain learning objectives. Additionally, in any class, some students will have prior business education knowledge and therefore can adapt to discovery learning quicker. For example, first-year students who were in high school business clubs, like DECA or Future Business Leaders of America, will grasp concepts far faster than others in an introductory business course. For students with little-to-no prior business knowledge, unguided discovery learning may not be compatible with their learning needs. They will struggle and take more time to find solutions, and that time might not fit within the semester.

Discovery learning fails if there’s no guidance to help students who have no prior subject knowledge.

Discovery learning may frustrate students, as they can easily get confused without a sufficient conceptual foundation to serve as a framework. Regardless of the motivation, the endless wandering to seek answers can drive students to just prioritize completion without learning—especially if they are constantly balancing multiple courses. They may perceive the experience bitterly and lose enjoyment and interest in the learning.

McKinsey also found that students had lower learning outcomes in classes with high levels of inquiry-based teaching without a sufficient foundation of teacher direction. Although discovery learning seems ideal for tackling the challenges of engagement, knowledge retention, critical thinking, and creativity, the approach fails if there’s no guidance to help students who have no prior subject knowledge.

Discovery learning is inherently more challenging to deliver effectively, so professors without proper training and support may not be able to drive the intended learning outcomes. When students go through an autonomous learning process, professors serve as mentors who can drastically support or hinder students’ progress toward discovering solutions. Professors who are not well-prepared and do not anticipate students’ questions can impede the discovery learning journey as they struggle to provide helpful guidance and feedback.

Blended Pedagogy: The Best of Both Worlds

If direct instruction fails to teach students critical thinking skills, and discovery learning can leave students floundering, it seems logical that the ideal instructional method is a blended approach. In fact, McKinsey’s analysis supports this conclusion.

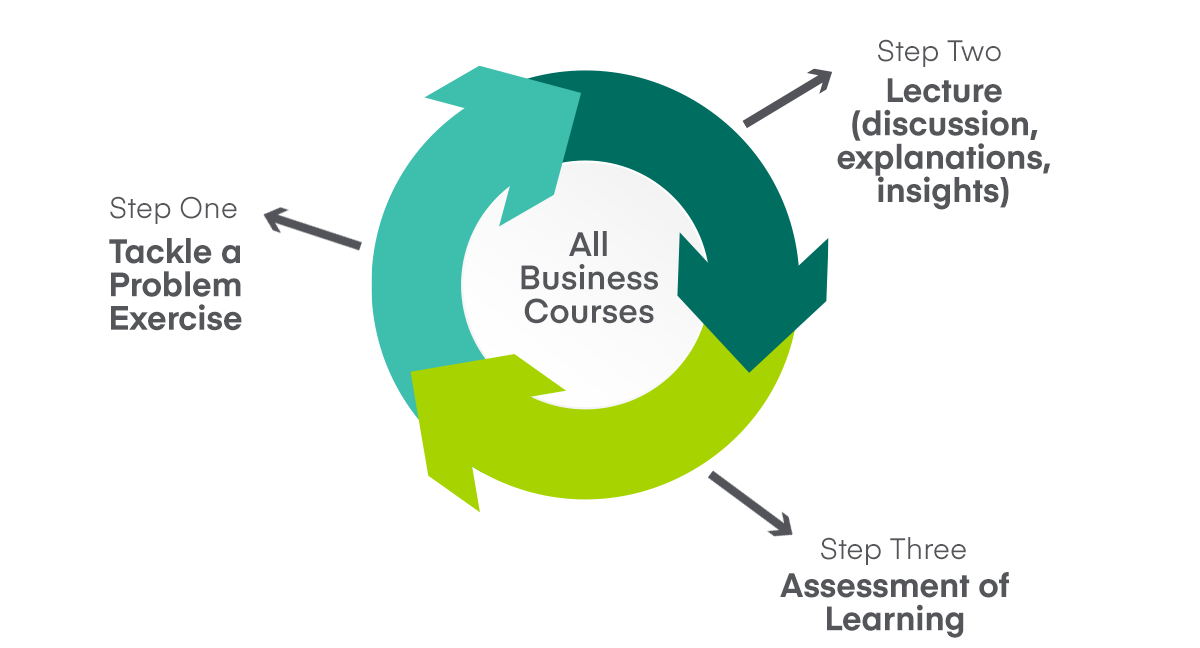

Figure 1. Blended Pedagogy Model for Business Courses

It’s very clear that instruction should be incorporated into most learning activities. What we are proposing is for professors to lead not with a lecture but instead with a problem. A learning exercise can deliver insights to professors, drive engagement with students, and spark rich in-class discussions for all.

For example, an instructor might provide students with a real-world problem to tackle prior to class. This could be a mini-case study that takes students on a learning journey of inquiry and decision-making as they wrestle with ambiguity. Class time would then be spent on lively discussions led by the professor, who guides the class in analyzing and synthesizing the case from many angles.

Several other examples demonstrate blended learning in practice, as provided by my colleagues.

The Integrated Core Experience program at the University of Virginia’s McIntire School of Commerce in Charlottesville operates in similar fashion, but it's far more ambitious: more than 300 undergraduates within one course tackle real client problems presented at the beginning of the semester. To help students build the foundational skills needed to solve these unstructured complex problems, commerce professor Kisha Lashley and her colleagues utilize the case study method and take students on a semesterlong guided discovery process, which ends with students presenting their solution to corporate executives.

Miami University’s Farmer School of Business in Oxford, Ohio, takes it a step further by introducing real client projects to more than 800 students in their first year. In Farmer’s First-Year Integrated Core program, professors Cindy Oakenfull, Harshini Siriwardane, and Justin McGlothin also use a combination of instructions and exercises to help build critical thinking and teamwork skills for the client project. This includes the use of a business simulation to help first-year students experience how business works while building team rapport prior to tackling the client project.

Critical thinking is a mental skill that students need to practice and refine over time, and it starts with active learning.

As an alternative to a semesterlong project, a professor could create mini projects using a “flipped” classroom approach. In this scenario, instruction is provided first, but not during class time. At the University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business in Iowa City, finance professor Jon Garfinkel provides instruction prior to class through pre-recorded lectures. He then spends his entire class time guiding students as they work through real-world exercises in teams.

The professors who prepare tomorrow’s leaders must ensure that they train undergraduate students to research, investigate, and ask questions to find solutions to problems. This type of critical thinking is a mental skill that students need to practice and refine over time, and it starts with active learning. Direct instruction pedagogy is an effective and efficient way to teach factual knowledge, but a curriculum built primarily on it would be limiting for students’ learning potential in a business classroom.

Shaping Ideal Leaders

Self-directed learning can help students generalize learning to novel tasks and subsequently make content stick. Most importantly, it can help students hone their critical thinking, creativity, and cooperation skills; strengthen their motivation; and boost their belief in their business acumen. As they develop confidence in their capabilities, they will become eager to pursue a career in the related field.

In the 21st-century business world, graduates who possess adequate critical thinking and other soft skills are highly demanded by recruiters because those graduates will not just follow instructions. They will think outside of the box and look beyond what they are given to drive results.

As educators, we have the power to shape students into ideal business leaders of tomorrow if we focus on designing a curriculum that better reflects the realistic business workplace.

Torsor Kotee is founder of the ed-tech startup, Market Games.