Circadian Rhythms and the Future of Work

- The post-pandemic workplace is defined by three pillars: flexibility, technological advancement, and locational ambidexterity.

- Employers should take into consideration three biological factors that affect the physical and mental health of workers: chronotype, circadian biology, and time of day.

- As much as possible, workers should be allowed design their work schedules to match their genetically predetermined chronotypes, so that they can optimize their performance and well-being.

In 1996, flip phones were popular and Netscape was the leading internet provider, connecting users to 100,000 websites. This also was the year that Jeremy Rifkin wrote The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era. In his landmark book, Rifkin predicted a transformed global economy and the displacement of workers by new technologies.

Since 1996, many of his predictions have come to pass. But three additional shifts have occurred that have substantially impacted the employment and psychological contract between organizations and workers. The first occurred during the 2008–2009 financial crisis, when workers lost their jobs and sense of security; the second, during the COVID-19 global pandemic, when lockdowns and business closures reshaped the way we live and work; and the third is taking place right now with higher levels of inflation and interest rates.

These shifts have had a range of consequences, not the least of which is reduced life expectancy. A December 2022 article in The Wall Street Journal notes that U.S. citizens now live 76.4 years, on average, decreasing from 78.8 years in 2021—the lowest level since 1996. In other words, employees’ lives have been upended—and, it appears, also shortened—by a number of factors.

The unfolding story for the next generation of workers and leaders can be captured by new terms that have emerged since the pandemic: The Great Resignation, quiet quitting, and career cushioning. Given all the changes they have endured, it’s not surprising that today’s workers have become increasingly disillusioned.

How can business schools help students, faculty, and staff prepare for a future of work characterized by so much change and uncertainty? How can they help employers design workplaces that support worker well-being?

One way, I believe, is to recognize—and accommodate—three biological factors that are critical in optimizing worker productivity and mental and physical health. These include chronotype, circadian biology, and the time of day best suited to completing individual tasks.

The Implications of Hybrid Work

These factors have become especially important given the way COVID-19 has changed the way people work. In particular, pandemic-era changes have reinforced three pillars that characterize the future of work: flexibility, technology, and ambidexterity.

Flexibility. The pandemic set in motion a trend in which more workers can choose where, when, how, and even why they work. Workers are seeking not only greater flexibility and work-life balance, but also greater purpose and meaning in their jobs.

Technological advancement. Innovations that companies adopted to cope with the impact of the pandemic—such as videoconferencing, mobile technologies, cloud computing, and collaborative virtual workspaces—have proven effective and efficient. Now, three years later, these new ways of working have withstood the test of time.

Locational ambidexterity. As institutions and employers reopen their physical campuses and offices, a new workplace competency is emerging—ambidexterity, otherwise known as the ability to conduct work in hybrid formats. Employers have discovered that many workers can perform at consistently high levels, often at a lower cost, when they have options to work from home at least part of the time.

Taken together, these three pillars give employees more freedom to create their own schedules, rather than clocking in and out like factory assembly-line workers. Moreover, when working remotely, employees regain the time they once spent commuting back and forth—which for some could have been as much as an hour and a half each day. Many are now asking new questions about how they want to spend this extra time:

- When do I want to wake up and go to bed if I don’t have to commute or punch a clock?

- How can I align my work schedule with my genetically determined chronotype?

- How can I synchronize my ideal work times with those of my colleagues during collaborative work?

- Could I benefit from “power naps” during the “midday slump”?

- Could I benefit from taking microbreaks throughout the day, such as taking walks (even during meetings) or going out to enjoy the sunlight?

These questions have implications beyond workers and employers. As online and hybrid courses become more popular, business schools also must consider such questions as they deliver courses that suit the individual preferences and schedules of their students and faculty.

Know Your Chronotype

In 2017, three scientists won the Nobel Prize for discovering the “body clock” gene. They found that we are all born with one of three chronotypes: morning, intermediate, and evening.

As mentioned earlier, your chronotype is genetically determined—you can no more change your chronotype than your eye color or height. It is not a personality quirk or preference; it is your biological reality. The key to success is to match your chronotype with the challenges of the day.

Your chronotype is not a personality quirk or preference; it is your biological reality. The key to success is to match your chronotype with the challenges of the day.

In an ideal world, faculty, staff, and students would choose work schedules, tasks, and courses based upon their chronotypes to optimize performance and lessen distress. For instance, if your chronotype favors early morning, you should front-load your most important tasks in the morning when you’re feeling most productive.

Honor Circadian Biology

Many birds sing at dawn and at dusk, and many flowers open up during the day and close at night. Like other living organisms, humans also respond to the rising and the setting of the sun. It makes sense, then, to expose yourself to natural sunlight and fresh air as soon as you awaken each day—especially during the winter months—as well as in the middle of the day around the afternoon slump.

Scientists say that natural sunlight exposure gives you a boost of energy akin to drinking a cup of coffee, but without the caffeine. Sunlight exposure can help deepen your focus and enhance your ability to perform. In an ideal world, offices and classrooms would have windows and robust air exchange systems to enable everyone to benefit from the energy-boosting effects of natural sunlight and fresh air.

Mind the Time of Day

In his 2019 book WHEN: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing, Daniel Pink delves into the difference that the right timing can make in your working and personal lives. Simply put, when it comes to engaging in activities such as problem-solving, decision-making, creating, and relating to others, the time of day matters.

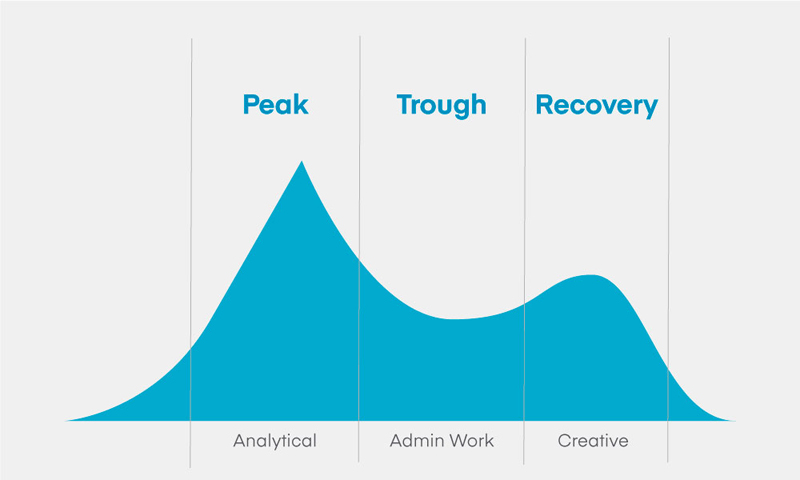

Our daily cycles are divided into three stages: peak, trough, and recovery. To optimize performance, you should do intensive analytical work when your energy is at its peak and more routine administrative tasks during the trough. Then, you can save more creative work for the recovery phase.

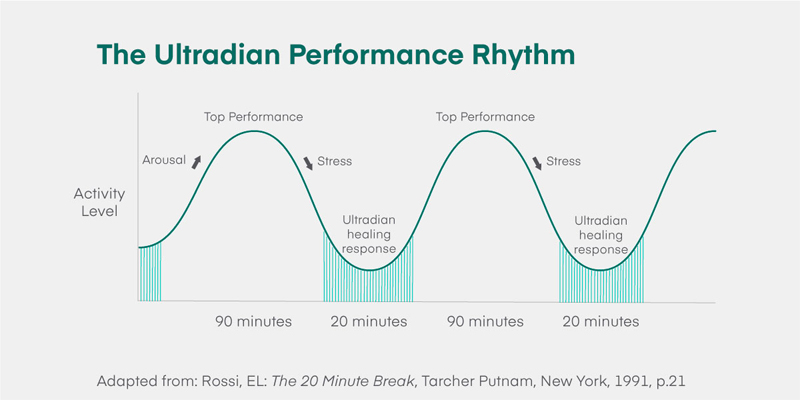

However, not everyone’s peak time is the same. Each person’s day has a biologically determined rhythm—what scientists refer to as an ultradian performance rhythm.

For example, one of my research collaborators is a night owl (similar to about 15 percent of the working adult population). She begins her day at about 1 p.m. and teaches her courses in the late afternoon and evening. I, on the other hand, am an early riser, so it’s best if I complete my analytical work in the early morning and creative tasks in the early afternoon and evening.

Our performance is optimal when we flow with our natural rhythm, working with full attention and intention for a set period, before purposefully disconnecting from work for another set period. This is not a novel concept—many religions rest on the Sabbath Day, while individuals often take sabbaticals from their jobs. In real-world terms, companies might normalize taking 10-minute breaks between 50-minute meetings, as a way to buffer against “Zoom fatigue.”

What’s important is that, during your “off” periods, you engage in activities that allow you to rest, recover, rejuvenate, recharge, or relate to others. You should not switch to another work-related or stressful task.

As Alex Soojung-Kim Pang writes in his book Rest, “If you want rest, you have to take it. You have to resist the lure of busyness, make time for rest, take it seriously, and protect it from a world that is intent on stealing it.”

Right Time = Best Performance

Imagine that you are a professor who serves on three committees that each meets at 10:30 a.m. It takes you 45 minutes to commute to campus. You also teach two courses each semester, including a hybrid course that meets at 1 p.m. and an online course, which you teach over Zoom, that starts at 8 a.m.

If you are an evening chronotype, these tasks will not be aligned with your peak, trough, and recovery phases. In that case, how would this schedule affect your mental, emotional, and physical health? How would it affect your energy levels and attention, likelihood of making mistakes, and even your ability to emotionally regulate when dealing with challenging students and colleagues?

We all are given the gift of 1440 minutes each day. Whenever possible, we should be allowed to optimize this finite resource by syncing specific tasks with the times of day that work best for our genetic makeup.

In a world where employers understand the importance of chronotype, circadian biology, and timing, you could ask your supervisor for opportunities to align specific tasks such as teaching, writing, and collaborating with particular times of day. As much as possible, you could arrange your schedule to maximize, rather than limit, your performance, productivity, and well-being.

The Impact of Common Biases

If you happen to be a supervisor, it’s important for you to avoid two common biases that could cause you to minimize employees’ scheduling concerns:

False consensus bias: The assumption that everybody has, or should have, the same chronotype as you do. It is true that most folks (about 70 percent) are intermediate chronotypes. But that means that nearly one out of every three people is either morning or evening chronotypes (about 15 percent each).

Flexibility bias: The assumption that, in order to be productive, employees must be working at the office, in the chairs at their desks, at specific hours of the day. But we now know that as long as workers achieve desired outcomes and deliverables, there is no need for employers to engage in “place-checking,” “chair-checking,” and “time-checking.”

We all are given the gift of 1440 minutes each day. Whenever possible, we should be allowed to optimize this finite resource by syncing specific tasks with the times of day that work best for our genetic makeup.

The Future Is Here

Before the pandemic, we viewed scenes from The Jetsons and Star Wars that depicted people using different technological tools, working at different times and from different places, and collaborating with each other over video screens as futuristic. But COVID-19 accelerated the shift to the future of work. Developments that we once thought unimaginable are now commonplace.

The pandemic brought with it changes that have reshaped our world, particularly along the three pillars of flexibility, technological advancement, and locational ambidexterity. As a result, we all must rethink the physical and chronological boundaries of our working lives. The workplace is transforming, just as Rifkin predicted. The future of work is here. In that case, we must ask ourselves a critical question: Will we respond to this new reality with closed or open minds?