Distance Learning: The Top 10 Practices

Even before the arrival of COVID-19, higher education was becoming increasingly virtual. Once the pandemic took hold, schools around the world quickly transitioned to online delivery, and professors began looking for simple solutions they could enact quickly to make their classes more engaging. Advice about online learning abounds. But how can faculty sift through all the options to determine the best way to deliver courses online? Which approaches have the optimal impact on the student learning experience?

We are part of a Committee to Advance Teaching and Learning (CATL) at Bowling Green State University (BGSU) in Ohio. When the pandemic struck, Ray Braun, dean of the Schmidthorst College of Business, charged the CATL with crafting and implementing a rapid response plan for the school. We soon realized that one of our most pressing responsibilities was to identify the minimum specifications for asynchronous distance learning courses.

Our first step was to create a preliminary laundry list of these minimum requirements by reviewing the literature and asking faculty open-ended questions about the fast transition to online learning. Our second step was to seek input from BGSU’s department chairs and program directors. They had two urgent recommendations: Keep the list concise, and avoid labeling the items on our list as “minimum requirements,” because faculty might find such language too controlling. By taking both of these recommendations seriously, we were able to distill our list into The Ten Core Practices Essential to Distance Learning Experiences.

Drawing General Conclusions

Despite the work we have done so far, our document is a work in progress. To make certain that we have identified the best core practices, we have administered a survey to faculty and students at BGSU, as well as four faculty colleagues from other institutions. Of the 161 responses, roughly 54 percent were from faculty and 44 percent from students. While we will continue to examine the data for more insights, we have drawn several key conclusions.

First, these are the right core practices. Almost 94 percent of faculty and 100 percent of students agree with this statement: “Overall, this set of ten core practices accurately represents the essential elements for a quality distance learning experience.” More than 96 percent of the total respondents rank the top practice as important, while even the tenth practice on the list is considered important by 66 percent. And while the two groups assign different weight to some practices, they both prize practical mechanics over active learning experiences.

The three Priority A practices focus on clear communication, content, and feedback.

Therefore, we created and ranked four categories within the ten core elements. The three Priority A practices focus on clear communication, content, and feedback; each one has a total importance score of more than 90 percent. The Priority B practices revolve around creating learning spaces where all students feel safe and included; the ones in this grouping all have a score of 85 percent or better.

Priority C,which is unique enough to be in a category all by itself, deals with academic integrity; it has a rating of almost 84 percent. The Priority D practices facilitate an engaging and meaningful interactive experience; the three items in this category all rate 80 or below.

Respondents consider all ten core practices useful for a quality distance learning experience. By prioritizing some over others, we are basically separating the good ones from the great ones.

In the coming months, we will continue to update an online repository of resources, which will be made available through the LibGuides maintained by BGSU’s University Libraries. But for now, here is the current list.

The Ten Core Practices

No. 1: Provide a variety of relevant and timely feedback.

Total importance: 96.1%

Instructor importance: 94.4%

Student importance: 98.2%

In addition to offering feedback, the instructor creates mechanisms that foster student-to-student feedback (peer and double loop learning). This ensures that students focus on their own learning, believe the feedback is credible, and stay motivated to improve themselves.

No. 2: Keep students informed with regular communication.

Total importance: 94.9%

Instructor importance: 97.2%

Student importance: 96.5%

The instructor sends communications on a predictable basis using a standard medium. This promotes consistency and efficiency in the course, enables students to be proactive, increases confidence, reduces stress, and fosters learning safety.

No. 3: Curate content that is accessible to all students.

Total importance: 92.2%

Instructor importance: 90.1%

Student importance: 94.9%

The instructor provides content, including lectures, in mixed media forms that allow students to read, listen, view, and engage with the material. Because students want to be more prepared for class events and assignments, they intentionally study the information in advance, which enables the instructor to build upon the content with active learning experiences.

No 4: Coordinate all activities, events, and due dates though a central calendar.

Total importance: 87.6%

Instructor importance: 86.1%

Student importance: 89.5%

When students can set notifications and access calendar information on multiple devices, they can manage their own time, take responsibility for their learning, and be accountable for their coursework.

5. Create a two-way conversation with students.

Total importance: 86.8%

Instructor importance: 87.3%

Student importance: 86.0%

The instructor proactively meets with students both synchronously during live activities and asynchronously in forums. This creates a sense of connection between students and the instructor, increases the instructor's presence within the class, and builds a trusting relationship among all the classmates.

6. Ensure the students’ user experience is friendly and sticky.

Total importance: 86.2%

Instructor importance: 88.9%

Student importance: 82.7%

The instructor provides a concise, appealing, and easy-to-navigate online structure and setup for the course. This encourages students to leverage learning management system features that save time for themselves and for faculty, while reducing errors.

7. Protect the academic honesty and integrity of the course.

Total importance: 83.8%

Instructor importance: 88.9%

Student importance: 77.6%

The instructor creates valid and reliable assessment procedures that mitigate cheating. This ensures the course is fair, is respected by students, provides a useful evaluation of learning outcomes for accrediting bodies, and maintains the integrity of the degree program and the university.

8. Build a learning scaffold of activities that require the use of course content.

Total importance: 80.0%

Instructor importance: 84.7%

Student importance: 74.1%>

The instructor develops an integrated set of relevant tasks in which assignments build on each other and students must draw on course content to complete them. In this way, students move beyond rote learning, which is at a lower level of learning on Bloom’s taxonomy, and enter into enduring learning, which is at a higher level on the taxonomy. They also acquire skills they will use in their professional pursuits.

9. Facilitate an engaging collaborative learning community.

Total importance: 78.7%

Instructor importance: 77.2%

Student importance: 80.7%

The instructor creates activities in which students collaborate and engage with each other on a deep and reflective level. This healthy learning community experience encourages peer-to-peer support, reduces confusion, and increases student commitment for all aspects of the course.

10. Frame the learning outcomes in ways that are meaningful.

Total importance: 66.2%

Instructor importance: 63.9%

Student importance: 68.9%>

The instructor explains how the learning outcomes connect to all elements of the course, as well as to students’ professional and personal aims. When students understand the “why” behind the entire course and its specific components, they are inspired to do their best work and bring their best selves.

Assigning Priorities

We determined the importance of the various practices by holding discussions with focus groups and analyzing open-ended questions on the survey. These methods also enabled us to identify specific activities within each priority that instructors can implement to improve their online teaching.

Priority A: Ensure clear communication, content, and feedback. One theme runs through the three most critical core practices: Let students know what is happening, how to get started, what content to focus on, and how they are doing in terms of their grades. Students want faculty to eliminate clutter, confusing information, and extraneous material while organizing content in a way that makes resources efficient, effective, and reliable.

It’s interesting to note that more students than faculty say it is “very important” for instructors to provide timely feedback and create accessible content. This indicates that instructors who improve in these areas have an opportunity to make a deeply positive impact on student learning.

To meet student expectations in these areas, faculty can take three steps:

- Provide feedback on all assessments within one week of the due date. Use the learning management system’s rubrics for scoring assignments and giving customized feedback.

- Send a weekly update to the class via a central communication medium such as the announcements feature in the LMS. Follow that up with reminders that offer tips and encouragement.

- Curate a concise set of relevant and accessible resources, supported by recorded lectures and instructional videos, to demonstrate how content connects with assignments and testing.

Priority B: Create a safe, well-organized learning space that includes all students.Students want a course and instructor they can respect, while the instructor wants students who are committed to the course. Instructors should focus on being present and organized in the classroom, while deploying an LMS that is easy for students to use and navigate. They should use technology to send students reminders of due dates, so they can coordinate assignments quickly and efficiently. Finally, they should be sure that students can find a live person at the other end of their devices—a real teacher who shows care and concern for them.

To achieve these goals, faculty can implement three practices:

- Publish the course as a soft launch before the start date; include an overview video. After class has started, hold live orientations, followed up with regular office hours.

- Centralize all due dates and events within the LMS calendar. Require students to use the notifications feature and download the app to their devices.

- Respond to student questions within 24 hours. Meet with students via video conferencing to address specific questions, perhaps by using the online calendar to offer sign-up times in 15-minute increments.

Students want to undnerstand how the course connects to the things that matter in their professoinal and personal lives.

Priority C: Protect the academic honesty and integrity of the course.Students want to know that the class is fair and just, while faculty want to ensure assessments are valid and reliable. But faculty have additional concerns about course integrity: They want to make sure students don’t cheat during tests, and they want to be certain all students are doing their own work.

To address these issues, faculty should work with the IT department and teaching technology experts to verify that the “real” students are taking the tests and submitting assignments. Faculty also can implement three specific actions:

- Build a test bank in which the questions, responses, and order of questions are different each time. This creates a unique test—and assessment—for each student.

- Apply plagiarism checker technology like Turnitin or Grammarly. In the assignment instructions, clearly state this technology will be used.

- Communicate the rules both in video and writing. Let students know how the school is gathering digital evidence of cheating and what the consequences will be for academic dishonesty.

Priority D: Facilitate an engaging and meaningful interactive experience. Students want to understand the purpose of the course and how it connects to the things that matter to them in their professional and personal lives. They also want to know that the instructors are passionate about what they’re teaching.

Why do respondents rate these final practices as important, but less critical than other activities? Perhaps because both instructors and learners are exhibiting subtle resistance to the pedagogical approaches touted as the future of higher education. Perhaps because deep, collaborative learning experiences are time-consuming both for instructors and students. Faculty and students simultaneously want and don’t want to put in the effort to master these deep learning activities.

Nonetheless, faculty can take three steps to implement these practices:

- Create discussion groups where drafts of assignments are posted. Require students to review and comment on each other’s work, and base part of their grades on interaction.

- Leverage the LMS’ adaptive release features, which allow instructors to make more content available when students achieve certain milestones. One way to implement adaptive release is to give out iterative assignments that build learning scaffolds; new assignments draw on the competencies that students have just mastered.

- Give a problem that can’t be solved, requiring students to use resources to get started. Then host a synchronous session using breakout groups to formalize and submit a solution.

Drawing It All Together

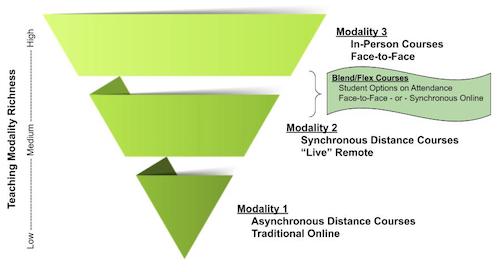

Previous research has examined the “richness” of various teaching modalities. (See illustration below.) Currently, asynchronous distance courses have the lowest level of teaching richness, synchronous distance courses have an intermediate level, and in-person classrooms are the richest. Many schools also are offering blended or flex courses that allow some students to attend in person, while others attend via live video conferencing. The model below suggests that, as teaching modalities become richer, students and instructors will exchange more information and participants will interact more meaningfully with others in the class.

The Hierarchy of Richness in Teaching Modalities

The ten core practices outlined here can add richness to any level of the teaching hierarchy. In fact, one of our survey respondents commented that this list “doesn’t just apply to online, remote classes. All classes need all ten!”

We think of our ten basic principles as similar to the hierarchy of human basic needs. As humans, we can’t focus on higher-order needs such as social interaction and self-actualization until after we have satisfied basic needs such as oxygen, water, food, and shelter. Likewise, with online learning and teaching, it makes no sense for us to focus on deep learning activities until we have the basic competencies in place.

To reiterate, this means that faculty should start with providing clear feedback, communication, and content. Then they should create safe learning spaces that support diverse styles and foster assessment integrity. Only when those priorities are in place should they focus on practices that promote active learning.

Good teaching practice is a labor of love. Faculty must be in tune with their students and adapt as needed, learning as they go. One survey respondent made the case very clearly, writing, “Care about your students as individuals. Not every student fits into every plan. … Know that in order to reach a student, you may have to modify guidelines. If students are having a hard time … then just send them an e-mail or heaven forbid, pick up the phone and help them. What’s going to happen if you do? They might just succeed.”

By identifying the ten core learning practices, we hope to put faculty on the path to helping every student succeed—especially when they are delivering courses through online learning.

This paper was produced with Peter VanderHart, a professor in the Schmidthorst College, in conjunction with the university’s Committee to Advance Teaching and Learning.