Experiential Learning in a COVID World

Project-based experientiallearning has become increasingly embedded in the MBA curricula of U.S. schools. A 2020 survey by the professional networking group LEPE (MBA Leaders in Experiential Project-based Education) showed that 58 percent of responding business schools require students to take an experiential learning course to graduate, and another 21 percent include an experiential learning requirement for at least some concentrations. Moreover, 43 percent of respondents invite students from other master’s programs and undergraduate programs to participate on project teams.

Similarly, a 2020 survey by experiential learning platform provider EduSourced showed that, of the responding business schools, 87 percent offer project-based experiential learning programs. Thirty-eight percent require students to take at least one experiential learning course.

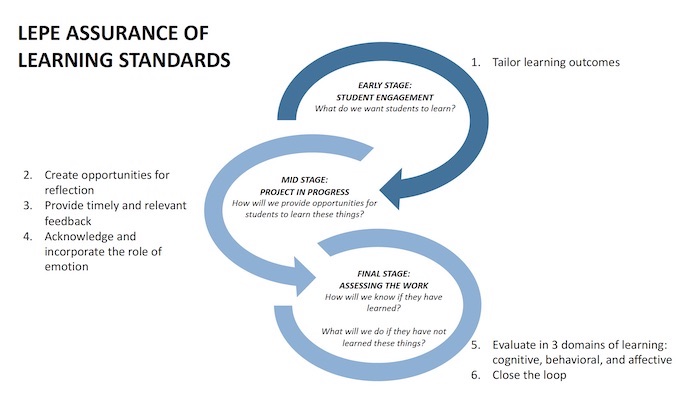

In a 2018 article, we shared six strategies that business schools with mature experiential learning courses have adopted to deliver project-based experiences with the best learning outcomes:

1. Tailor learning outcomes.

2. Create opportunities for reflection.

3. Provide timely and relevant feedback.

4. Acknowledge and incorporate the role of emotion.

5. Evaluate the three domains of learning: cognitive, behavioral, and affective.

6. Close the loop.

Since then, we have mapped these standards to different stages of project work (see the graphic below), and we have used surveys and conference sessions to monitor how institutions across the LEPE network are implementing them. We believe schools can use these standards both to evaluate student learning and to advocate for change.

Focus on Learning

The LEPE standards define the success of project-based experiences by focusing on student learning. This differs from other common measures, which focus more on inputs—such as experiences completed, students served, and new programs established—and student satisfaction.

For example, the OnSite Global Consulting course at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth in Hanover, New Hampshire, has always incorporated 360-degree feedback. While students were compliant about completing the necessary assessments, there was a great deal of variation in the type of peer feedback. Therefore, the course shifted to an assessment based on the quality of feedback and now provides more resources to help students give and receive feedback effectively.

In another example, the Fuqua Client Consulting Practicum at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business in Durham, North Carolina, wanted deeper insights into how well students were performing in the three domains of learning: cognitive, behavioral, and affective. The school piloted a modified peer feedback survey that included reflection prompts on the three areas. In one instance, peers noted that a student had mastered the cognitive domain but performed poorly in the behavioral domain, specifically in terms of punctuality, inclusion, and communication. A standard feedback survey most likely would have highlighted the cognitive achievements of this student while sweeping aside affective and behavioral problems.

Focus on Change

Because the six standards are informed by at least four years of survey data gathered from a range of schools, they give educators a starting point for advocating for change and continuous improvement.

In LEPE surveys conducted between 2018 and 2020, we asked schools which two of the six standards they felt they were most successful at implementing. In 2020, “creating opportunities for reflection” scored 72 percent and “providing timely and relevant feedback” was at 56 percent. These results are unsurprising, as feedback and reflection have long been core tenets of many management education programs, and both are relatively easy to implement and measure.

But during the past two years, schools have gained confidence in how well they meet the standard of “tailoring outcomes to individuals.” The percentage of schools that felt it was one of the two standards they were implementing most successfully has risen from from 20 percent in 2018 to 41 percent in 2020. One school has determined that every project should include two one-on-one meetings between students and faculty advisors. Before the meetings, advisors can consider both individual student goals and unofficial midpoint grades so they can assess how well students are progressing.

The LEPE standards define the success of project-based experiences by focusing on student learning.

The standards that schools feel they are least successful at implementing have remained the same since 2018: “evaluating students in three domains of learning” (cited by 66 percent) and “acknowledging the role of emotions” (63 percent).

We believe the problem comes down to execution. We have proposed a toolkit, but we realize that it could represent a heavy drain on resources. For instance, we encourage schools to train advisors and staff to let students know, during orientation, what typical emotions they might feel at different stages of an experiential learning project and to monitor this throughout. We also suggest that schools use pulse checks to monitor and track team emotions. For many schools, implementation of these two standards could build on practices already in place.

Despite the challenges, many schools are relying on the standards we have outlined to guide them toward improving their programs. In our 2020 survey, 40 percent indicated that their revisions would be related to one of these six standards. Administrators saw two primary barriers to success: lack of resources (according to 28 percent) and the ongoing effects of COVID-19 (24 percent).

Focus on the Future

Indeed, COVID-19 has had a severe impact on experiential learning programs, and programs involving spring break travel immersions were hit particularly hard in March 2020. Anecdotal feedback suggests a similar impact for spring 2021.

Once the virus subsides, a vigorous period of innovation will be needed—one that goes beyond incremental tweaks. Among other changes, schools will need to develop new ways to leverage their virtual platforms, which allow schools to enhance their offerings in three primary ways:

By increasing accessibility. For instance, the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge recently reinvented its Global Entrepreneurship Lab to help students better grasp the economic, policy, and healthcare-related impacts of COVID-19 in different geographies and industries. Conducting the project virtually allowed the school to open it to students from across the institution and form cross-disciplinary teams.

By creating new partnership opportunities. The OnSite Global Consulting course at the Tuck School has developed a similar offering in partnership with Aoyama Business School at Aoyama Gakuin University in Tokyo. This fall, students from the two schools joined forces with a staff team at a Japanese manufacturing company to study market trends and opportunities for nonmedical face masks. Because of funding constraints, such a program would not have been possible if travel had been required.

By exposing students to new destinations—and more of them. A new course at the Smith School of Business at the University of Maryland in College Park will expose students to five countries instead of just one. Most institutions could not dream of entertaining such a plan if students were expected to travel.

We see these exciting experiments not as replacements for field experiences, but as ways of extending those experiences while preparing students for the new normal.

Focus on Quality

Only if we are honest about what was not working before—and what we can gain and lose in a digital environment—will we see the emergence of new, innovative, cost-effective experiential learning models. Each of the six standards must adapt to virtual learning constraints and opportunities in the following ways:

By tailoring learning outcomes. In digital environments, it is even more important to ask students to share their individual learning goals. This keeps them grounded and reminds them why they should engage in the work.

By creating opportunities for reflection. In virtual interactions, faculty can use the chat function to pose a question of the week so students can share observations. Students can gather in breakout rooms for small-group reflection sessions. Instructors can opt for frequent, brief reflection checks or longer sessions that occur less often.

Broader and more frequent feedback is needed in the virtual setting.

By providing timely and relevant feedback. Broader and more frequent feedback is needed in the virtual setting. Faculty should not only schedule regular check-ins to monitor individual and team progress, but also think carefully about how and when they provide feedback. They can make use of online features for tiny feedback messages (for example “reactions” or celebration features in Zoom), in addition to relying on more formal mechanisms.

By acknowledging and incorporating the role of emotion. Because students are under varying levels of stress right now, faculty must be hypervigilant about student emotion. It is more important than ever that instructors consider student feelings as data.

By evaluating the three domains of learning. Online platforms allow instructors to use public and private forums to design and assess learning objectives in the areas of cognition, behavior, and affect. Such platforms also allow students to give each other feedback.

By closing the loop. In the virtual environment, professors can take advantage of natural pauses to evaluate courses, while increasing the frequency of assessment. They also can solicit student feedback to make sure courses are aligned with the needs and expectations of learners. These check-ins are all the more important because visual cues are often missing or blunted in a virtual format.

The primary focus of the LEPE standards is to facilitate the student’s ability to learn from experience. The standards also allow schools to pivot quickly by ensuring that educators design new experiences with student needs in mind. Whether classes meet in the field or online, the standards provide a true north for designing high-quality experiential learning programs.