‘Lift Up the Cherished Blossoms’

Advising undergraduate students is a big job, especially when up to half of incoming students are transferring from somewhere else. Incoming students need guidance on a wide range of topics: major selection, course options, campus resources, graduation requirements, housing and financial aid possibilities, scholarship and exchange opportunities, and job prospects.

At the College of Business and Economics at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, advising responsibilities historically have been distributed among professional and faculty advisors. Each incoming student was assigned to a professional advisor in student services during the first year, before being handed off to a major-specific faculty member. Over the years, to address perceived gaps in advising, we added special program advisors in areas such as student support services, disability services, minority access and achievement programs, international study, and athletics.

Unfortunately, having plural advisors created its own issues. With so many cooks in the kitchen, students often received contradictory advice. Even the most well-intentioned faculty advisors often could not stay up-to-date on ever-changing general education, transfer, and graduation requirements. Students reported being told to take courses that didn’t count toward their majors, to take two different classes that fulfilled the same requirement, or to put off difficult classes, which then delayed their graduation. Others were stressed because they missed transfer credits or received incorrect information. Furthermore, having to visit a multitude of offices often left students feeling adrift.

It was no secret that students were dissatisfied with their advising experience. For years, the university’s annual exit survey had surfaced “inadequate advising” as a significant obstacle to timely graduation. Semester after semester, our students requested a single advising contact in the college, but we were unable to get the resources to implement such a program.

A Shift in Priorities

The opportunity to change our approach came when Emmeline de Pillis, one of the co-authors of this article, became department chair. She directed faculty to send all difficult advising questions (aka “level-two tech support”) directly to her. While this improved both the faculty and the student experience, the chair was now spending half her time on advising, which crowded out her other duties. During registration periods, she had a line of students stretching down the hallway. Many of the students’ issues were the result of earlier misadvising. It was clear that if students had been reached earlier, with more accurate information, many problems could have been avoided.

Knowing that there was no additional money to support college-based advising, we proposed a cost-neutral option, which was accepted by administrators after some negotiating. We traded away a department chair position and transferred to the dean’s office some department chair duties such as course scheduling. In exchange, we asked for summer pay and course overloads to support an academic success coach—an instructor whose primary service obligation was advising students. In this way, advising would become a high priority for one faculty member, rather than a low priority for everyone.

We wanted to give our program a name that not only conveyed its philosophy, but also acknowledged the host culture and our role as a Native Hawaiian-serving institution. We are indebted to Keiki Kawaiʻaeʻa, director of Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani College of Hawaiian Language, for the name Kaʻipualei, which means “direct and lift up the cherished blossoms.”

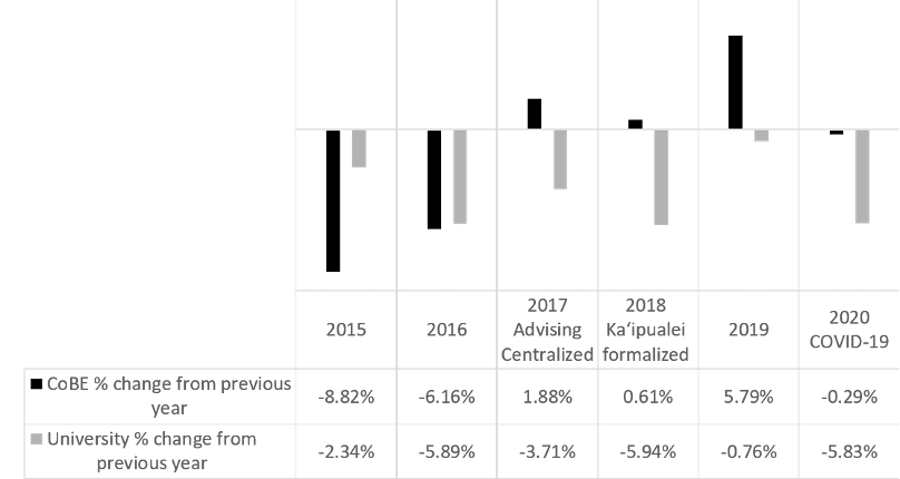

The introduction of the Kaʻipualei program appeared to reverse enrollment decline in the College of Business and Economics, while the rest of the university continued to lose headcount.

The centerpiece of the Kaʻipualei model is the academic success coach (ASC)—currently Helen Tien, the other co-author of this article. As the first point of advising contact, she provides academic and career advising to our majors, minors, and certificate-seekers. She also pre-screens student requests for prerequisite overrides, helps students plan their course schedules, participates in campuswide outreach activities, performs unofficial graduation checks, and works with other offices to resolve students’ issues.

Kaʻipualei at the University

At the university level, professional advisors are still the first stop for incoming students. Because the ASC has built productive relationships with the professional advisors, the sophomore-year handoff is a smoother and more personalized process. In addition, because the ASC teaches required courses, the students are likely to know her already as an instructor when they come in for advising.

While the ASC is the central point of contact for business students, she frequently directs them to other people on campus with the right expertise. But she calls ahead to find the right office and individual to address each student’s issue.

The ASC also lifts the burden from professors, who no longer have to puzzle their way through gen-ed transfer questions, graduation checks, or other technical issues. Professors still can mentor students within their areas of expertise—and they have more time to do so.

Our Results So Far

We examined the records of all 770 students who entered the College of Business and Economics as anything other than temporary exchange students between the years of 2016 and 2020. Of these, 51 percent were female, and 42 percent were transfer students. While students ranged from 17 to 66 years old, the average age was 24.7. Currently, 52 percent are still enrolled, 25 percent have graduated, and 21 percent have dropped out with no degree.

Seventeen percent (133 students) participated in the Kaʻipualei program by meeting with the academic success coach at least once. These visits took place starting in 2019, when the program began. Of those 133 participants, 14 (or 10.5 percent) dropped out with no degree. Of the 638 students who did not participate in the program, 178 (or 27.9 percent) dropped out with no degree.

While this was not a randomized, blind study and there is always the issue of self-selection, we believe these early numbers are promising. Some other facts and figures:

Most ASC visits related to practical, prescriptive advising such as planning course schedules. Just over a quarter of the students who visited the ASC came with general advising questions; just under a quarter had questions about registration. Nineteen percent wanted to discuss internships, 14.4 percent were interested in course overrides or exchange course approvals, and 13.3 percent had 11th-hour graduation issues. The rest were looking for recommendation letters or wanted to change their majors.

The introduction of the Kaʻipualei program appeared to reverse enrollment decline in the College of Business and Economics. When the program was implemented, CoBE enrollment stabilized while the rest of the university continued to lose headcount, as evidenced by Table 1 below:

Table 1: CoBE Enrollment Levels Out

Participation in the Kaʻipualei program independently predicted dropout rates after correcting for other factors. To examine the effect of the Kaʻipualei program in the context of other established predictors, we used linear regression in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software to analyze a number of variables. These included age, gender, transfer status, and the higher of high school GPA and previous college GPA. We used “Dropped with no degree” status as the dependent variable.

Transfer status, previous GPA, and Kaʻipualei participation were all statistically significant predictors. Transfer students were more likely to drop out without a degree. Kaʻipualei participants and those with higher GPAs were significantly less likely to drop out. In fact, we found that 11.8 percent of the dropout rate was explained by the Kaʻipualei intervention.

Lessons Learned

If other schools want to replicate our program, we suggest they take four steps:

1. Hire the right individual for the job. The academic success coach must be energetic, creative, and skilled at working with others. The ASC must have a high level of initiative, but must avoid a “my way or the highway” approach. At our school, the ASC is an instructor with a 12-credit teaching load, and she also spends 10 to 30 hours a week advising students. Because of those time commitments, she is not expected to be actively publishing as well.

2. Keep complete records of advising interactions. At our school, each time the ASC meets with an advisee, she briefly notes the gist of the meeting on the student’s electronic record, which can also be accessed by the professional advisors and the registrar. She keeps a record of impromptu drop-in meetings as well as scheduled meetings. This allows for consistency both over time and with different departments such as financial aid or the registrar’s office.

3. Provide basic information. We found that most students who sought advising were looking for the basics. What can I take that fits my schedule? How can I graduate as quickly as possible? While empathy and relatability are wonderful characteristics, they mean little to students who aren’t getting the information they seek.

Most important, the model works. Students who make at least one visit to the Kaʻipualei academic success coach are significantly less likely to drop out.

4. Offer online scheduling. Our ASC teaches during the semester, which means she is not available for walk-in consultations when she is in class. An online appointment calendar is important for students’ convenience and peace of mind. Walk-ins are welcome, but online appointments take priority.

Early Success

Students have been pleased with the new position, as evidenced by these comments:

- “It’s nice to have someone who knows your career interests from an early start so that they can help you plan your degree, down to specific electives.”

- “I am grateful for the current one dedicated business advisor model. The advisor is aware of all moving pieces.”

- “Through my dedicated business advisor, I was able to create an actionable plan to both complete my degree and discover my career interests.”

- “It was so helpful to have a dedicated advisor that knew of my study abroad situation and ensured my course transfer steps.”

- “Because of CoBE’s advising model, I graduated with a job offer and tremendous appreciation for the value of my degree.”

The Kaʻipualei model is cost-effective, because it uses a central advisor who also serves as an instructor and because it consolidates general and major-specific expertise in a single office.

But most important, the model works. As our data show, students who make at least one visit to the Kaʻipualei academic success coach are significantly less likely to drop out, which is a win for the students and the university alike.