Women in Business: One School’s Story

In 1956, Rita (Zekas) Sielicki applied to Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., to study accounting. Four years later, she was the first woman to graduate from what would become the McDonough School of Business. Even though she was literally the only woman in the room in her business classes, Sielicki found opportunities to lead, becoming an officer in the Accounting Club and several other organizations. After graduation, she found a job, married a Georgetown classmate, and juggled being in the workforce with being a young parent before pausing her career until her children were older and more self-sufficient.

Like many of the women who were the first to study at co-ed universities, Sielicki learned her first lessons about management while working in her family’s Pennsylvania business. As the pioneering work of historian Anne Firor Scott has shown, this “pre-training” was traditional for many early women leaders, who developed their skills while leading women’s civic groups long before they had opportunities for formal leadership roles.

To mark the achievement of Georgetown’s first female business graduate, and to honor the women who came after her, the McDonough School recently published 60 Years of Alumnae–Memories, Milestones, and Momentum. Sielicki’s story is one of many that helps paint a picture of the struggles and rewards women experienced as they studied business in the last half of the 20th century.

A Series of Common Themes

A team of 40 students, faculty, and staff from McDonough spent three years documenting the history of the women who graduated from our school. Students in the first two decades earned undergraduate degrees in business administration, while students who came later were often enrolled in MBA and other master’s degree programs.

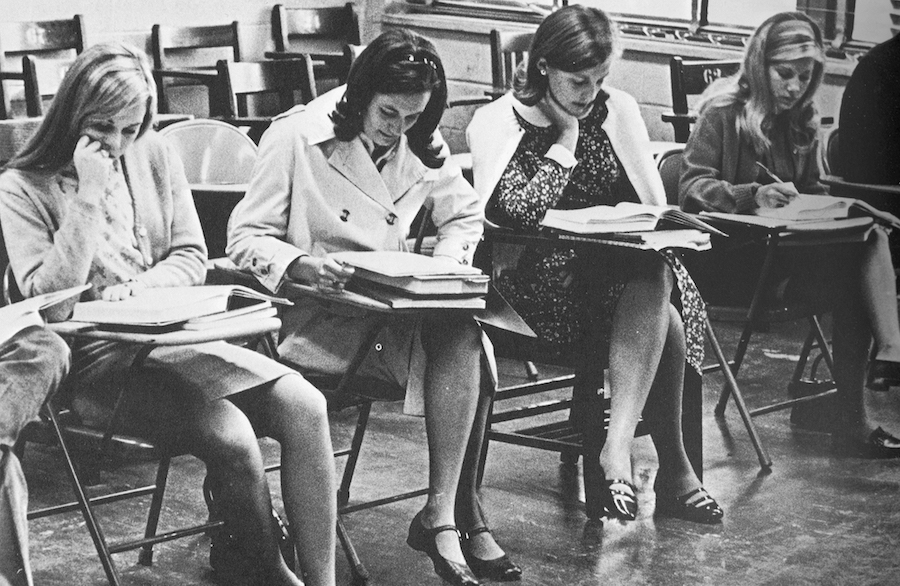

Women attend Georgetown University business classes in 1969. Photo courtesy of Georgetown University.

Simply identifying our earliest alumnae was a challenge. At that time, student records were not electronic, none were coded for a student’s gender (or race and ethnicity), many included only the first initials of students, and women’s surnames often changed quickly after graduation if they married. Accounting for these alumnae and then following their careers were painstaking tasks. The ones we did interview couldn’t always help us find other women from their classes, because most women lived off campus. Furthermore, there were so few of them that they didn’t necessarily cross paths.

However, it’s difficult to tell the story of any group if you cannot count its members, and we were determined to identify our early alumnae. As we continued our research, we learned a tremendous amount about these women. We also noted some common themes:

They defied workplace norms. We expected that some of these early women students might graduate and slide into fairly traditional roles, but our expectations were upended. A willingness—even an enthusiasm—to be one of very few women in a group seems to come with a willingness to defy other norms as well.

Many of our first graduates went on to earn second degrees, including PhDs, JDs, and MBAs. They also started companies, ran major nonprofits, argued cases before the Supreme Court, served on state supreme courts, took over their families’ businesses, worked all over the world, and served in critical financial agencies like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

They were internationally minded. During the first ten years that women enrolled in our business school, they were surprisingly international. For example, in 1962, the third largest cluster of these students came from outside the United States. By the end of that first decade, 23 percent of women business graduates were from Asia, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America.

Once they graduated, these women had a global orientation long before “global” was a buzzword. They fanned out around the world, serving in nonprofits and other organizations where their leadership skills helped strengthen healthcare, education, and business. In many cases, their international work was tied to their husbands’ careers, but they also built on their early global experiences to stake their own strong personal claims to leadership and the study of women’s leadership.

The graduates of the 1980s and 1990s committed to creating systems and processes to accelerate the careers of alumnae who came after them.

They paved the way and broke through. This accomplishment is perfectly embodied by Teresa Iannaconi, who earned an MBA in 1978, became a partner at KPMG, and held a position at the SEC; she also earned a Georgetown JD when she was 72 years old. But she shattered the norms of one of her employers by having a child. During her first pregnancy, the partner in charge of her office said, “I am sorry, but you will have to leave. We can’t send a pregnant auditor out to client offices.” Iannaconi replied, “I don’t know what your problem is with that, but there is no physical reason you could not.” It was the first time the firm decided to allow a pregnant woman to continue working rather than let her go.

Iannaconi notes that her boldness “broke the policy of that firm, and the next year when another newly hired woman got pregnant, she never even had to discuss the matter.” To be clear, the company changed its policies to avoid litigation, which was a common motivation then. It would take decades—with significant progress still to be made in 2021—before firms began to see both the moral and business cases for diversity.

Fellow 1960s alumnae faced a workplace that was less hostile but more clueless. Maurine Mills, who graduated first in her class in 1968, recalled that in 1972 her Wall Street employers “didn’t want to take me to any client meetings because they weren’t really sure how that would go over.” By the mid-1970s, women’s enrollments were increasing fivefold in business, and at even higher rates in other disciplines. However, women like Lynn Tamburo, who graduated in 1974, still talked about being “in that glass-ceiling era … where we were really pioneers in the business world.”

They supported other women. The graduates of the 1980s and 1990s—who had few corporate role models to guide them—committed to creating systems and processes to accelerate the careers of alumnae who came after them. They often were the first women in previously all-male bastions of business, law, and government, and they started some of the first women’s leadership groups and mentoring programs in their firms.

For instance, in the male-dominated world of beer production, Julie Kinch, who earned a bachelor’s degree in 1982, rose to be chief legal counsel at Heineken. Because her own rise had been so challenging, Kinch reflected, “I had a platform and an obligation to help other women in the company. This is what first motivated me to start the women’s leadership group” at Heineken.

Others used their experiences to ensure that women and underrepresented minority entrepreneurs would have access to capital. For instance, Melissa Bradley started 1863 Ventures, which is dedicated to helping Black and brown entrepreneurs accelerate their enterprises. Bradley, who is an adjunct professor at Georgetown, notes that only 34 Black women founders have raised more than 1 million USD in venture funding; her goal is to raise more than 100 million USD to help at least 1,863 more do so. 1863 is the year that the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in the U.S., changing the legal status of enslaved African Americans to free.

Keeping the Momentum Going

As we wrote the book, our team found many business schools and organizations striving to advance women’s leadership in business. We also discovered research by our faculty and other scholars that identified key and ongoing issues:

- Mentorship, sponsorship, and allyship are all vital.

- Access to venture capital and the entrepreneurial ecosystem is essential for future women entrepreneurs.

- Women juggling work and motherhood require creative options and supportive organizations.

- Women’s success hinges on many different steps—including choice of majors while in school, careful selection of career-enhancing roles, and strategic assumption of promotion-enhancing assignments.

- Gender is critically intertwined with race, religion, and culture. Leaders must address these issues in tandem, not in isolation.

Uncovering these important lessons is the first step. Now, we must build on the achievements of our faculty and alumnae to keep their momentum going.

Gender is critically intertwined with race, religion, and culture. Leaders must address these issues in tandem, not in isolation.

In addition to my role as a professor at Georgetown, I lead Custom Executive Education at the McDonough School of Business. Over the last two years, my team has taken these lessons to heart and designed a series of customized programs for corporate and nonprofit clients who are committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Those programs on women’s leadership and organizational equity have now enrolled hundreds of men and women from more than 25 countries; many have become champions for DEI in their own organizations.

Within our degree programs, our faculty also teach courses on women’s leadership; inclusion and innovation; and ethical leadership, which addresses issues of social justice. We also just announced that six faculty, three students, and a staff member will work as inaugural Baker Trust/McDonough DEI Fellows beginning this summer and continuing into the academic year. Their goal will be to increase the diversity of the content in our core courses and support faculty who want to address DEI in their classes.

As we finished researching 60 years of Georgetown’s history, involving more than 6,000 amazing alumnae, we were left with a sense of optimism. Over the past six decades, the paths have been rocky for women graduates of business schools. We know that, during the next six decades, the paths ahead will not be smoother unless we make a focused effort. The business and moral cases for DEI are clear and undeniable, and we must show our commitment to that conviction.